From the first minutes of the Zoom call, I sense that Clare* is down. Sighing heavily, she tells me she feels like a fraud. Despite her glittering CV, she worries if her promotion to CEO has been a mistake and worries what her colleagues will think of her when she is found out. Clare is not alone. Feeling like an impostor at work is common, and leaders are not immune. In a 2022 survey of 500 UK business leaders, 78% reported experiencing impostorism.

Coined in 1978 by psychologists Pauline Clance and Suzanne Imes, the ‘impostor phenomenon’ describes feeling like a fraud despite evidence of achievement, and fear of being found out. They used ‘phenomenon’ as opposed to the more commonly referenced ‘syndrome’ intentionally – reasoning that it is a natural experience, not a clinical disorder.

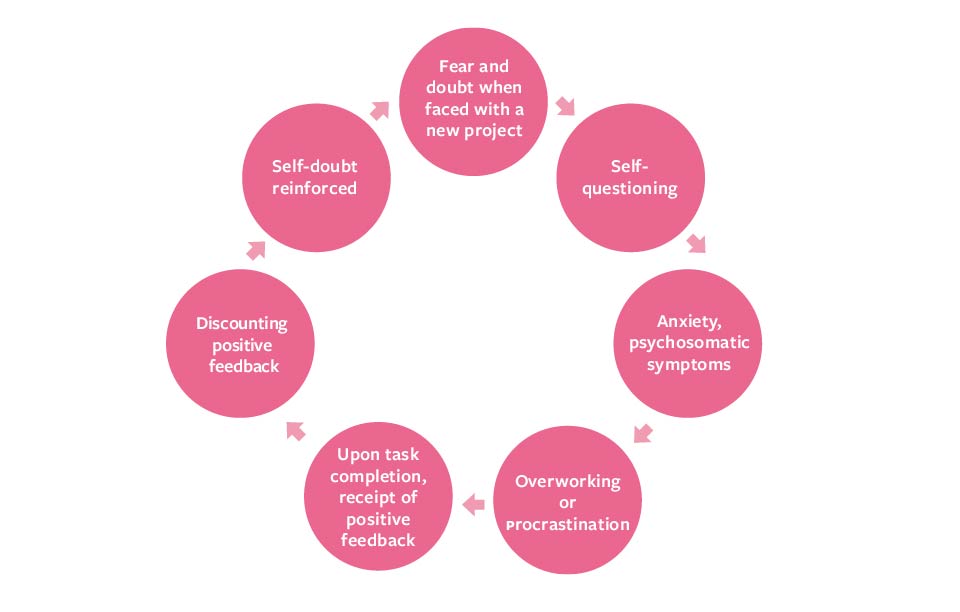

Yet for those affected, the impostor phenomenon can feel debilitating (see Figure 1). Leaders may be especially vulnerable, with elevated expectations placed upon them, along with high levels of responsibility and visibility.

Speak about it

When we talk about thoughts and feelings of impostorism, they become just that – thoughts and feelings, not facts. Speaking out creates a psychological distance whereby impostorism moves from a spirit within us to a more distant, if annoying, niggle. Playfulness can help – one client envisaged their impostorism as a devil cartoon character to be swatted away like a fly. The impostor cycle may be deep rooted, so vocalising successes regularly is important. This helps us selectively attend to the evidence of achievements we might ignore, training our brain to think more helpfully over the long term.

In a virtuous cycle, speaking out can help others too. In 2010, Professor of Physiology Melanie Stefan proposed publishing a ‘CV of failures’ to expose the multiple setbacks behind any single success. While acknowledging the embarrassment this might cause, she argued it could help build perspective, motivate and empower. Talking honestly about our highs and lows, including our fleeting moments of impostorism, may be viewed not as a weakness, but as courageous leadership.

Learn it all, not know it all

Managing impostorism is not just an ethical responsibility but is fundamental to organisational success. Individuals who feel like impostors may be more risk averse and less adaptable, leaving them more likely to shun innovation, and shy away from challenging opportunities.

“Managing impostorism is not just an ethical responsibility but is fundamental to organisational success”

To remedy impostorism in themselves and others, leaders can boost psychological safety by promoting a growth mindset culture and knowledge sharing. They can prioritise ‘learn it all’ over ‘know it all’, and act as role models by showing it is acceptable to make mistakes in the pursuit of innovation, and essential to speak up about mistakes in the interest of safety.

While research suggests minorities may be more susceptible to feeling like an impostor, causal links are unclear. Some reject the concept of impostorism altogether, asserting that discrimination and subtle microaggressions make people feel unworthy and unwelcome, not internal cognitive distortions.

Meanwhile Professor Kevin Cokley, an expert on impostor phenomenon among minoritised populations, maintains that people of colour experience impostorism just like anyone, but their feelings may also be rational reactions to racism, and these feelings interact. People may feel like impostors when they are treated in ways to suggest they are. Impostor feelings can be mitigated when individuals are treated as a person of value and worth. Leaders might reflect critically on the organisational climate to check for bias. Focus groups, anonymous surveys and informal discussions can help provide useful temperature checks.

Provide support

Leaders who prioritise clear, specific feedback as part of regular performance reviews help create a culture of open communication in which impostor feelings can be acknowledged and addressed.

Transparent career progression programmes, thoughtfully designed mentoring schemes, one-to-one, strengths-based coaching, and wellbeing policies, such as explicit expectations regarding not emailing outside of work hours, may help. Support may be especially beneficial for employees stepping up in their careers as enhanced responsibilities and visibility take their toll.

Yet, despite these efforts, some may still struggle. Non-work factors, including family upbringing and individual personality traits such as perfectionism, have been shown to slightly increase vulnerability to impostorism. Research shows that men and women both experience impostorism, albeit differently, with men tending to react more strongly to negative feedback, for example. While recognising the significance of individual context, a recent meta-analysis found that women may experience the impostor phenomenon slightly more frequently and intensely than men.

Fleeting feelings of impostorism are normal. They may be managed by interventions such as coaching and mentoring, and they may dampen naturally with leadership experience. Interestingly, while the imposter phenomenon is associated with increased levels of depression and anxiety, it has also been linked to certain positive traits, such as modesty. People experiencing impostorism may be preoccupied about what others think of them, but also more aware of others’ needs. In small, brief doses, the impostor phenomenon might just show us how to be a better leader.

As for Clare, she is thriving. After exploring her values and strengths, her attention shifted away from from a concern of what her team thinks of her, to concern for her team.

*Name changed for confidentiality.

Figure 1 Adapted from Clance & O’Toole, The Imposter Phenomenon. Women & Therapy, 6(3) (1987)

Seven ways to help manage impostor phenomenon

1. Assess. Rate the state of your wellbeing, including nutrition, exercise, sleep and hormones. Note down thoughts, feelings and coping behaviours over at least one week.

2. Personalise tools. Consider appropriate action based on your notes. For example, if you feel lonely, lean into your social circles; if you feel exhausted, prioritise rest.

3. Normalise. Impostor phenomenon is a natural emotion to be managed. Try to step back from feeling ashamed to noticing your emotions and let them go.

4. Commit. Move on from asking how and why, and commit to action. Embrace giving and receiving clear, specific, constructive feedback.

5. Seek out support. Learning about other people’s experiences can help build perspective. Join a support group, reach out to a mentor, or engage with like-minded friends.

6. Speak out. Talking dismantles shame, normalises feelings and creates distance from the impostorism. It also helps others.

7. Experiment with risk, reward effort. Aim to lean into discomfort (not pain). Celebrate the process of trying, not just achievement. Prioritise ‘learn it all’ over ‘know it all’.

Nina Hobson is a coaching tutor and coach at Barefoot Coaching.

This article is adapted from a feature first published in the summer 2025 issue of Edge